The Subtropical Advantage

A Climatological and Agronomic Substantiation of Florida as the Premier Jurisdiction for Commercial Cannabis sativa L. Cultivation

For decades, the Emerald Triangle held the crown. But a rigorous analysis of solar physics, plant physiology, and agricultural risk management reveals a fundamental realignment—Florida is the future of American cannabis.

Shifting the Paradigm of North American Cannabis Cultivation

The cultivation of Cannabis sativa L. in North America has, for the better part of a century, been inextricably linked to the “Emerald Triangle” of Northern California and the cool, maritime forests of the Pacific Northwest. This geographical anchoring was driven less by optimal agronomic principles and more by the exigencies of prohibition—remote, rugged terrain provided necessary concealment.

However, as the legal and regulatory landscape of the United States evolves toward commercial industrialization, the criteria for selecting cultivation sites have shifted from concealment to agronomic efficiency, climatological stability, and risk-adjusted Return on Assets (ROA).

Florida emerges through data-driven analysis as the optimal jurisdiction for large-scale, perpetual-harvest cannabis production.

A rigorous, multidisciplinary analysis of solar radiation physics, plant physiology, atmospheric dynamics, and agricultural risk management suggests a fundamental realignment of the cultivation map. Florida, often dismissed due to historical misconceptions regarding humidity management, emerges through data-driven analysis as the optimal jurisdiction for large-scale, perpetual-harvest cannabis production.

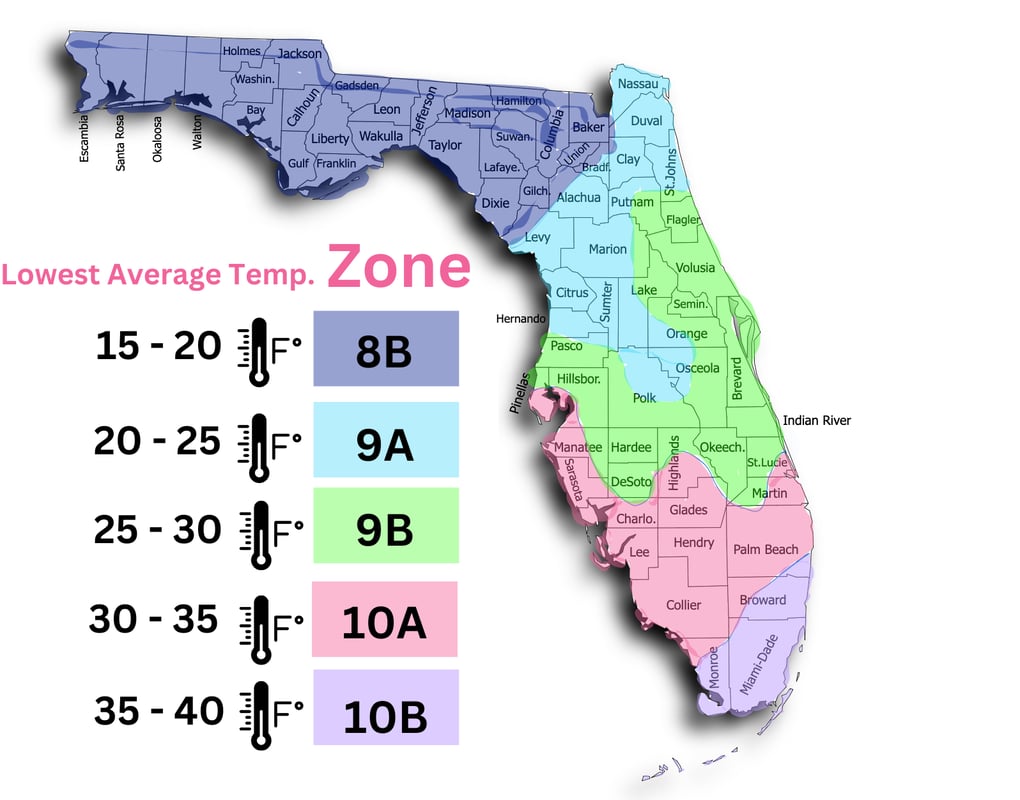

While California and Texas possess distinct agricultural strengths, Florida’s unique subtropical latitude (approx. 24°N to 31°N) provides a photoperiodic and radiative environment that facilitates year-round biomass accumulation without the prohibitive energy expenditures required in higher latitudes.

The Core Thesis

By synthesizing data on Daily Light Integrals (DLI), Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD) dynamics, and comparative catastrophic risk profiles—specifically the uninsurable threat of wildfire smoke taint in the West versus the engineerable risk of Atlantic hurricanes—we demonstrate that Florida represents the apex of modern, resilient cannabis agriculture.

Photoperiodism and Solar Radiation: The Physics of Yield

The fundamental currency of agriculture is the photon. In the context of C. sativa, a high-light energy crop, the accumulation of Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) drives the Calvin Cycle, biomass accumulation, and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (cannabinoids and terpenes). The geographic positioning of Florida confers a distinct, immutable advantage in the capture and utilization of this solar currency.

The Latitudinal Imperative

The primary limitation for year-round agriculture in the continental United States is the winter solar depression. As one moves north from the equator, the angle of solar incidence becomes increasingly acute during the winter months. This obliquity forces solar radiation to traverse a greater volume of the Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in significant attenuation of photon flux density.

In the traditional cultivation hubs of Humboldt County, California (40°N), and Southern Oregon (42°N), the winter solstice brings a profound deficit in solar energy. Data indicates that outdoor Daily Light Integral (DLI) values can plummet to 5–10 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ during December and January.

For commercial cannabis, which requires a DLI of roughly 25–30 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ for robust vegetative growth and 30–50 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ for maximal flowering density, these northern values are agronomically sub-critical. Cultivation requires massive inputs of supplemental lighting to bridge the “photon gap,” drastically increasing the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and carbon footprint.

Winter Daily Light Integral (DLI) Comparison

mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ — Higher is better for cannabis production

Contrastingly, Florida’s proximity to the equator maintains a significantly higher solar elevation angle throughout the boreal winter. In Miami-Dade County (25°N), the winter DLI rarely falls below 25 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹, staying well within the productive range for C. sativa without substantial artificial supplementation.

This “free” photonic energy allows Florida cultivators to maintain active photosynthetic rates year-round, converting solar energy into biomass at a lower marginal cost than their northern competitors.

| Parameter | Humboldt County, CA (40°N) | Miami-Dade, FL (25°N) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Solstice Day Length | ~9 hrs 15 min | ~10 hrs 32 min | FL provides >1.25 hrs more natural light/day in winter |

| Summer Solstice Day Length | ~15 hours | ~13 hrs 45 min | FL’s shorter days aid light deprivation efficiency |

| Winter Average DLI | < 15 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ | 25-35 mol·m⁻²·d⁻¹ | FL supports year-round photosynthesis |

| Solar Declination Variance | High Fluctuation | Low Fluctuation | Consistent growth enables factory-style planning |

Spectral Quality & Diffuse Radiation

Beyond the mere quantity of light, the quality of radiation in Florida offers distinct physiological benefits. The prevalent atmospheric moisture and cloud cover in Florida, often cited by critics as a detriment compared to the “clear skies” of Arizona or California, actually functions as a natural diffusion filter.

Direct beam radiation (typical of arid deserts) casts harsh shadows, often over-saturating the upper canopy (causing photoinhibition) while leaving the lower canopy in darkness. Diffuse light, scattered by water vapor and cloud cover, penetrates deeper into the plant canopy, reaching the lower leaves and axillary bud sites.

Radiation Use Efficiency

Research consistently demonstrates that for complex canopies like cannabis, a higher fraction of diffuse radiation increases the Radiation Use Efficiency (RUE) of the entire crop—resulting in more uniform flower development and higher Harvest Index.

The Photoperiodic Control Advantage

Cannabis sativa is fundamentally a short-day plant, with flowering triggered by lengthening nights. The critical photoperiod for most commercial cultivars lies between 12 and 14 hours of light.

In Northern California, summer days extend to 15 hours or more, keeping plants in a vegetative state until the autumn equinox—limiting cultivators to a single harvest cycle per year. In Florida, the longest day is roughly 13 hours 45 minutes.

Because Florida’s natural day length is never excessively long, the energy required for “light deprivation” (blackout curtains) to trigger flowering is minimal. Conversely, the “night interruption” lighting required to keep plants vegetative in winter is far less energy-intensive. Florida’s latitude provides a “neutral” canvas, allowing growers to manipulate the crop cycle with minimal energy inputs in either direction—facilitating perpetual harvest models.

Atmospheric Dynamics: Temperature, Humidity, and VPD

The climatic profile of Florida is characterized by high humidity and moderate heat. While this is often perceived as challenging for cannabis cultivation, a sophisticated understanding of Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD) reveals that Florida’s climate can be managed to create optimal growing conditions with proper infrastructure.

VPD—the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and how much moisture the air can hold when saturated—is the critical metric for understanding plant transpiration and nutrient uptake. The ideal VPD range for cannabis during flowering is approximately 1.0–1.5 kPa.

The VPD Advantage

Florida’s moderate temperatures (rarely exceeding 95°F even in summer) combined with proper dehumidification systems can maintain ideal VPD ranges year-round. Unlike the extreme heat of Texas or Arizona—which creates dangerously high VPD and forces stomatal closure—Florida allows continuous photosynthesis.

The key insight is that humidity can be removed; sunlight cannot be created. Florida’s abundant solar energy is a fixed, free resource. The challenge of managing humidity is an engineering problem with well-established solutions (dehumidification-first HVAC design, desiccant wheels, reheat coils). The challenge of insufficient winter light in northern latitudes requires ongoing, expensive energy inputs.

The Perpetual Harvest Model

The combination of consistent solar radiation, manageable temperatures, and controllable humidity enables what may be Florida’s most significant commercial advantage: the perpetual harvest model.

While California’s outdoor cultivators are limited to 1 harvest per year (constrained by the natural light cycle), and even their light-dep operations struggle with the extreme summer/winter solar differential, Florida’s consistent conditions allow for 3-4 complete crop cycles annually.

By leveraging modern greenhouse technology, Florida cultivators can achieve a perpetual harvest frequency that yields biomass output per hectare no other state can mathematically match.

Catastrophic Risk Analysis: Wildfire vs. Hurricane

Any serious agricultural investment must account for catastrophic risk. The comparative risk profiles of California and Florida reveal a stark asymmetry: California faces an uninsurable, unmitigable risk, while Florida faces an engineerable one.

Risk Profile Comparison

The distinction is fundamental: wildfire smoke contains volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol that chemically bond to the waxy trichomes of the cannabis flower. Even if a farm is not burned, smoke from a fire 100 miles away can contaminate the crop. This taint confers an “ashy” flavor and causes products to fail state-mandated testing.

In 2020 and 2021, vast percentages of the California cannabis harvest were compromised by smoke. In some counties, 100% of farms were affected. Insurance carriers are fleeing the California market entirely, leaving farmers self-insured against total loss.

Hurricane damage, by contrast, is kinetic (wind) and hydrologic (water). Unlike smoke taint, wind does not chemically alter plant chemistry. If the greenhouse holds, the crop is pristine. If salt spray occurs, it can often be washed off. Florida’s building codes—the strictest in the nation—provide a proven path to structural resilience.

| Risk Factor | California Wildfire | Florida Hurricane |

|---|---|---|

| Warning Lead Time | Minutes / Hours | Days / Weeks |

| Damage Vector | Fire + Chemical Taint | Wind + Water |

| Mitigation Strategy | Defensible Space (Low efficacy) | Structural Engineering (High efficacy) |

| Product Salvageability | Zero (Chemical damage) | High (If structure holds) |

| Insurance Market | Collapsing / Exclusions | Codified / Available |

Economic Benchmarking: Puerto Rico & Texas

The Puerto Rico “Island Tax”

Puerto Rico (18°N) is frequently cited as a competitor to Florida due to its deep tropical latitude and 12-hour photoperiod. However, benchmarking analysis reveals that Florida possesses the tropical advantages of PR without the infrastructure failures.

Puerto Rico’s grid (operated by LUMA/PREPA) is notoriously fragile, suffering from frequent blackouts and total collapse during storms. Electricity prices average $0.27–0.31 per kWh—nearly double the U.S. national average. To operate securely, cultivators must install massive redundancy (Tesla Powerwalls, diesel generators), drastically increasing CapEx.

Puerto Rico is also subject to the Jones Act, which requires goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on U.S.-flagged vessels, artificially inflating all imported agricultural inputs. Florida represents the “Mainland Tropics”—offering the solar profile of the Caribbean with First World infrastructure.

The Texas Continental Constraint

Texas, the other southern agricultural titan, offers vast land and high solar potential. However, it faces critical agronomic flaws for cannabis:

Texas summers are characterized by continental heat often exceeding 40°C (104°F) with extremely high VPD. This forces cannabis plants into prolonged midday depression, stunting yields. The 2021 winter storm highlighted the fragility of Texas infrastructure to cold—Florida’s winter threat is mild frost; Texas’s threat is a hard freeze that destroys plumbing and power grids.

Florida also has a robust, vertically integrated medical market with established regulations (MMTCs), while Texas remains restrictive, limiting commercial operations.

Optimal Infrastructure: The Florida-Optimized Greenhouse

To fully exploit Florida’s climatic advantages while neutralizing its risks, a specific infrastructure model is required. The “Florida-Optimized Greenhouse” must be distinct from Dutch-style glasshouses used in cold climates or the hoop houses of California.

Recommended Specifications

Purpose-built for Florida’s unique conditions

Structure

Gutter-connected, truss-reinforced steel frame with polycarbonate glazing. Impact resistance against debris + natural light diffusion.

Elevation

Facility pads raised 2–3 feet above the 100-year flood plain to mitigate hurricane storm surge risk.

HVAC Strategy

“Dehumidification-First” design with desiccant wheels or reheat coils. Maintain night-time VPD >1.0 kPa.

Water Management

100% rainwater capture from roof. Florida’s 50+” rainfall creates a self-sufficient irrigation loop.

Florida Is the Future of Cannabis

While the Emerald Triangle holds the romantic history of the plant, its future is clouded by the smoke of unmanageable wildfires. Puerto Rico offers the sun but lacks the power. Texas offers the land but burns the crop with continental heat. Florida stands alone at the intersection of agronomic abundance and infrastructural stability.